News

MINING: The bitcoin network hash rate breached 300 exahashes per second at the end of last month and has remained above this new threshold during the month of March. In spite of numerous restructurings and bankruptcies among the largest institutional mining operations, the network continues to grow. Although this increase in hash rate makes it more difficult for a given miner to earn the bitcoin reward that comes with successfully mining a block, overall mining economics have improved materially over the past several weeks. This improvement is due to bitcoin price appreciation in dollar terms as well as an increase in user fees. Regarding this last factor, the use case of data inscription and ordinals has created a "buyer of last resort" for space in bitcoin blocks, adding incentive fees revenue for miners where block space would otherwise go unused.

Interested readers can find more detail on recent trends in bitcoin mining economics in addition to several other interesting charts showing on-chain activity in Glassnode's The Week Onchain newsletter. The topic of ordinals was covered as part of a more general discussion of bitcoin miner incentives in Episode 95 of Citadel Dispatch.

BUSINESS: Publicly-traded Block Inc. (NYSE: SQ) has been busy building in the bitcoin ecosystem. The company recently announced that it is rolling out a new business to facilitate access to the lightning network and is also working on a mining development kit aimed at enabling "new or better uses for bitcoin mining hardware."

LEGAL: There were several headlines this month regarding the use of digital currency as money. The South Dakota state legislature passed a bill to amend the state's Uniform Commercial Code in a way that would expressly prohibit the use of bitcoin (and other digital assets) as legal tender while allowing the use of a central bank digital currency as money. This bill was vetoed by the governor who noted that the bill would have put South Dakota citizens at a disadvantage in addition to creating risk of federal government overreach. The governor of Florida expressed similar concerns when he proposed legislation that would prohibit the use of a central bank digital currency as money in the state.

Reserved

From: Magic Internet Money

By Jesse Berger

Tilted: Debt from Thin Air

“This unique attribute of the banking business was discovered many centuries ago… bankers discovered that they could make loans merely by giving their promises to pay… In this way, banks began to create money.” - Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, “Modern Money Mechanics”

Control over fiat monetary policy is a private party, and ordinary people are not invited. Central banks retain the sole, discretionary ability to create currency by making new entries into their own private, unaudited ledger, and also to set the baseline interest rate for lending throughout their subservient banking system.

Once created, central banks deposit new currency with commercial banks, which distribute it through a process called “fractional-reserve banking.” This system grants commercial banks a license to create additional money that they do not possess, merely by issuing loans – credits – against existing deposits – debits – without actually withdrawing funds from those deposits. In other words, loans made by banks are not pre-existing funds lent from one account to another, properly balancing credits and debits.

Instead, they’re unsubstantiated paper promises, conjuring new credit entries from thin air, like pulling a rabbit out of a hat. This privileged practice, reserved only for banks, is the soil in which the fiat financial system grows its magic money trees. Loans, as the roots of those trees, are a key driver of today’s global economy, and since most debts are directly affected by interest rates, which are controlled by central banks, the resulting influence exerted by central banks over the global economy is unjustly magnified.

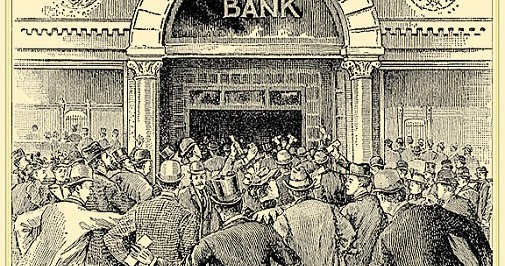

March 2023 marked what might be called the first bank run of the social media era. Prior depositor panics took days to play out via word of mouth and lines outside bank branches. By contrast, this month's fall of Silicon Valley Bank played out virtually overnight as concern spread at the speed of information through chat rooms and social media feeds, with depositors able to request outgoing wire transfers from the comfort of their couches. The contagion quickly spread throughout the regional banking sector. While the worst case scenario seems to have been prevented for now by the (increasingly ordinary) extraordinary actions of the Federal Reserve and US Treasury Department, the effects of this event have yet to play out entirely.

It's hard not to think of 2008 in connection with these recent events. As was the case back then, the central issue was a loss of confidence in the banks. In 2008, however, confidence was lost because no one had any idea what the assets of the banking system were worth, being as they were concentrated in sub-prime mortgages and derivatives of derivatives thereof. That is to say, there might have been $50 of capital at risk across the banking sector for every $1 of actual debt owed by a sub-prime borrower on short-term, adjustable rate loan collateralized by unaffordable house whose price was declining. Since that time, underwriting standards have improved. The vast majority of home loan borrowers today have sizable home equity cushions above the amount of their mortgage thanks to the rampant inflation experienced over the past five years. What's more, they've locked in long duration, fixed rate financing at a cost that is now below the yield on a US Treasury obligation. And therein lies the problem...

Depositors at US banks think they have tens of trillions of dollars of readily accessible cash. In reality, these depositors have IOUs from the banks which in turn have IOUs from businesses, owners of homes and cars, and the US government. Even though the banks are highly likely to get repaid in full on these loans, there is a mismatch between the duration of the banks' assets and liabilities. That is, if depositors were to withdraw more than a small fraction of their cash, the banks would not be able to cover the withdrawals because they can't demand immediate repayment from someone who borrowed a thirty-year fixed rate mortgage last year or from the US Treasury on a bond that doesn't mature for another ten years. So what is a bank to do?

Facing a wave of deposit outflows, a bank's only option is to raise cash by selling its assets to someone else. But if deposits are fleeing from the banking sector generally, who will be that someone else willing to buy the less liquid assets? What's more, after a year in which the Federal Reserve increased interest rates from effectively zero to 4.75%, the banks are trying to sell loans with interest rates locked in that are much lower than current market rates. Since the end of 2021, the average rate on a thirty-year fixed mortgage increased from around 3% to above 6.5%. So when a bank tries to sell a loan that carries 3% interest, it must do so at a sizable discount. A buyer looking to earn the current 6.5% market rate would pay no more than about 65 cents on the dollar to the selling bank.

Surely, the regulators can't allow this cascading loss of confidence, which begets withdrawals, which begets further pressure on banks' assets, which reduces confidence, which begets withdrawals, etc. And indeed, this is why the Federal Reserve and Treasury Department announced the aforementioned extraordinary measures. It's hard not to conclude that these measures will complicate the Fed's ongoing battle with stubborn inflation, and perhaps this is what the recent rise in the price of bitcoin is signalling. These episodes of depositor panic are inherent to our fractional reserve banking system. They are the primary justification for the existence of a central bank as the "lender of last resort" in the first place. But those last resort loans are made with money printed out of thin air, and this robs savers of a portion of the value of their life's work.

Maybe we ought to try something different.